The image for Day 271 0f the VM_365 project is of the two faces of a Stater, a coin struck from gold in the early first century A.D. , in the Late Iron Age. As the coin is made by placing a gold blank in a mould and striking it with a carved punch, the coin has a dish shape with one convex face and one concave. The example shown in the image was found with a metal detector in a field in St. Nicholas at Wade in Thanet.

Although it may seem that the value in finding coins like this comes from the metal they were made from, there is greater value in the knowledge that can be derived from the symbols that were used to decorate them and convey authority and value, as well as their distribution in the country. When coins are used to represent any sort of value in a society, they are often made from rare materials so they can not be easily copied, they are also decorated with images and words that also have cultural resonances in the society that accepts them. From these symbols we can make a culture that has left us no written evidence speak in its own voice in a small way. If we apply our current knowledge and understanding of coins and the economics of systems of exchange to the examples of ancient coins we discover, we can generate new ideas about how this type of material functioned in an ancient society.

On the reverse of this coin, which has a concave surface, there is a stylised rearing horse along with the letters CUN, representing CUNOBELINE the name of a King of the Catuvellauni tribe who took power in the first century to the late 40’s A.D. On the convex face of the obverse are the letters CAMU, showing the coin was minted at Camulodunum, now modern Colchester, one of the strongholds of the Catuvellauni and a centre of Cunobeline’s physical power. The precious metal, the name of the authority who issued the coin and the location of the mint assert the authenticity of the coin. That is not to say that as in the modern period coins could not be forged, but the technology set a barrier to reproduction and the authority of the power that issued it no doubt conveyed the punishment that might be applied to anyone caught producing them.

The distribution of the power and authority of the Kings who issued coins like this one can be estimated from their distribution pattern, which in this case is confined to the south east region. Perhaps people could take these out of the general area of circulation, but like most monetary systems they were potentially of more value circulating within the network of traders who recognised and accepted them while they were in this form as struck coins.

Because of the painstaking work to locate each coin discovered in archaeological excavations and by metal detectorists, we can assume that in the 1st century A.D. Thanet was within the territory of exchange with Cunobeline’s people, linking the many Iron Age archaeological sites in the area to the small scraps of written and symbolic evidence from coins which has been used to model Late Iron Age society. Many more Iron Age coins have been found on the Isle and the picture of overlapping powers and evidence for the exchange of currency in the Iron Age is so complex that a gallery in the Virtual Museum is dedicated to Iron coins in Thanet.

With thanks to David Holman for providing photographs of this coin.

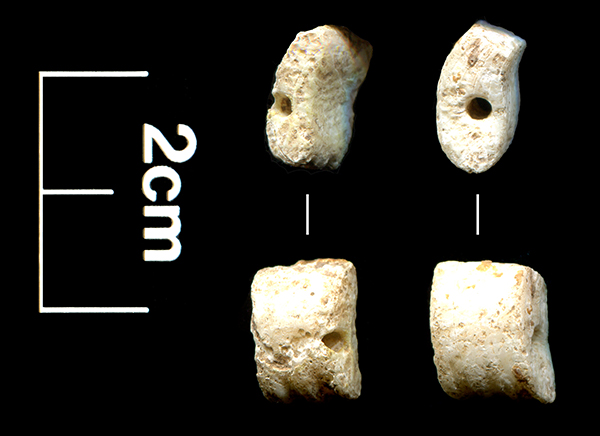

Today’s image for Day 275 of the VM_365 project shows four amber beads found in Grave 32 of the Monkton Anglo Saxon cemetery, part of which, was excavated in 1982.

Today’s image for Day 275 of the VM_365 project shows four amber beads found in Grave 32 of the Monkton Anglo Saxon cemetery, part of which, was excavated in 1982.

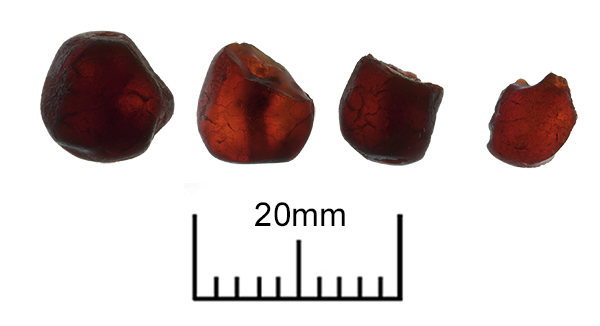

The image for Day 273 of the VM_365 project is of another coin dating to the Iron Age, a struck Bronze of a Late Iron Age King called Eppillus, which was found at Minster on the southern side of the Isle of Thanet .

The image for Day 273 of the VM_365 project is of another coin dating to the Iron Age, a struck Bronze of a Late Iron Age King called Eppillus, which was found at Minster on the southern side of the Isle of Thanet .

Today’s image for Day 270 of the VM_365 project shows a medieval copper alloy purse frame dating from the period 1474-1550 which spans the reigns of Edward IV, Edward V and Richard III. The purse frame was found in the excavation of a

Today’s image for Day 270 of the VM_365 project shows a medieval copper alloy purse frame dating from the period 1474-1550 which spans the reigns of Edward IV, Edward V and Richard III. The purse frame was found in the excavation of a