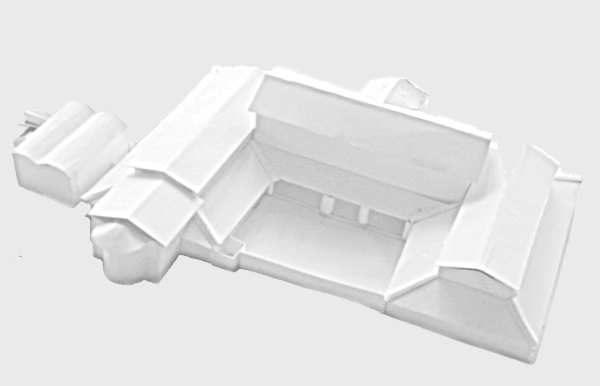

The image for Day 322 of the VM_365 project shows the eastern end of the church of St Mary the Virgin, Minster in Thanet. The church was constructed with a mixture of water rounded flints and Thanet beds sandstone, with Caen stone , Reigate stone and Ragstone used as dressings in the medieval period. Bathstone was used to construct some of the 19th century elements.

The image for Day 322 of the VM_365 project shows the eastern end of the church of St Mary the Virgin, Minster in Thanet. The church was constructed with a mixture of water rounded flints and Thanet beds sandstone, with Caen stone , Reigate stone and Ragstone used as dressings in the medieval period. Bathstone was used to construct some of the 19th century elements.

A nunnery was founded at Minster in the late seventh century, which existed until it was destroyed by Viking incursions in the early 11th century. A church on or near the location of the present church would have been associated with the nunnery from its foundation. This church would also have been the main church in Thanet. Minster became the mother church to the four chuches of St John the Baptist at Margate, St Lawrence at Ramsgate, St Peter at Broadstairs and All Saints, Birchington.

The church and the manor of Minster was given to St Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury in the early 11th century, when the monastic grange of Minster Abbey near the site of the present church which featured on Day 310 of the VM_365 project was established. The fabric of the present church originates in the Norman period, probably on the site of the earlier Anglo Saxon church building, although no evidence of the earlier church seems to survive in the the building.

The four churches of Minster, St John the Baptist, St Lawrence, and St Peter were possessions of St Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury unlike St Mary Magdalene, Monkton which featured on Day 317 of the VM_365 project and belonged to the estates of Christchurch Priory, Canterbury.

Parts of the early Norman church at Minster survive in the nave. The nave walls were pierced for arcades In the mid 12th century, to expand the space into newly constructed north and south aisles. In the late 12th century the western tower was added and in the lower sections of the tower reused Roman brick, probably originating from the nearby Roman villa at Abbey Farm, was used in its construction. The reused Roman brick can clearly be seen in the image above.

The eastern part of the church was rebuilt in the early 13th century, forming a cruciform church with large lancet lights. The outer walls of the south aisle and east part of the north aisle of the nave were rebuilt and new windows were inserted in the early 14th century.

Crown-post roofs were built in the 15th century and at the same time the top of the tower was rebuilt with a timber spire and a crenellated parapet. The stair-turret which can be seen on the right handside of the tower in the image above may also have been rebuilt at this time.

The church was heavily restored in the 1860’s, when the north aisle was completed as part of the restoration work.

References/Further Reading

Jones, H, and Berg, M. 2009. Norman Churches in the Canterbury Diocese. The History Press.

Tatton-Brown, T. 1996. St Mary Church, Minster in Thanet. Canterbury Diocese: Historical and Archaeological Survey. http://www.kentarchaeology.org.uk/01/03/MIT.htm

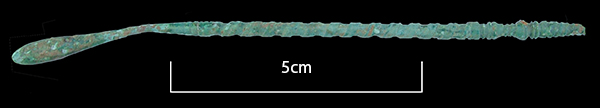

The image for Day 281 of the VM_365 project shows a copper alloy cast Roman Spoon-Probe found during the 1999 excavation season of the Roman villa at Minster.

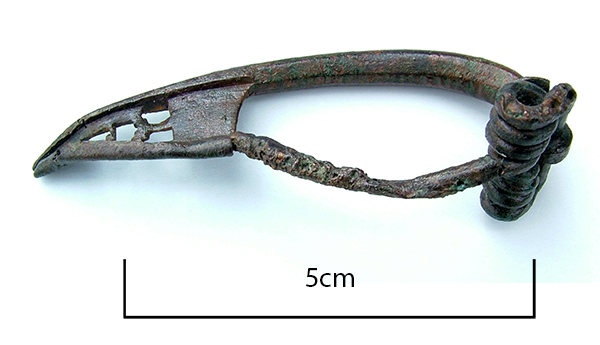

The image for Day 281 of the VM_365 project shows a copper alloy cast Roman Spoon-Probe found during the 1999 excavation season of the Roman villa at Minster. The image for Day 280 of the VM_365 project shows a Bow Brooch or Fibula of late Iron Age or Early Roman date, which was found in 1992 when trial trenching was carried out between Monkton and Minster in advance of the expansion of the old single lane road into a dual carriageway.

The image for Day 280 of the VM_365 project shows a Bow Brooch or Fibula of late Iron Age or Early Roman date, which was found in 1992 when trial trenching was carried out between Monkton and Minster in advance of the expansion of the old single lane road into a dual carriageway.

The image for Day 273 of the VM_365 project is of another coin dating to the Iron Age, a struck Bronze of a Late Iron Age King called Eppillus, which was found at Minster on the southern side of the Isle of Thanet .

The image for Day 273 of the VM_365 project is of another coin dating to the Iron Age, a struck Bronze of a Late Iron Age King called Eppillus, which was found at Minster on the southern side of the Isle of Thanet .